It has long been accepted and acknowledged that there is a link between a country’s research productivity and its economic progress, and this is one of the main motivations for investing a country’s valuable resources into research. A recent study by Jaffe et al. published in PLoS ONE [1] analyzed the research productivity of various countries in relation to their economic status, and further showed that there are “aspects of the relationships among disciplines, and between those disciplines and countries’ economic development.” This highlights the synergistic relationship between a country’s present research structure and its future economic growth.

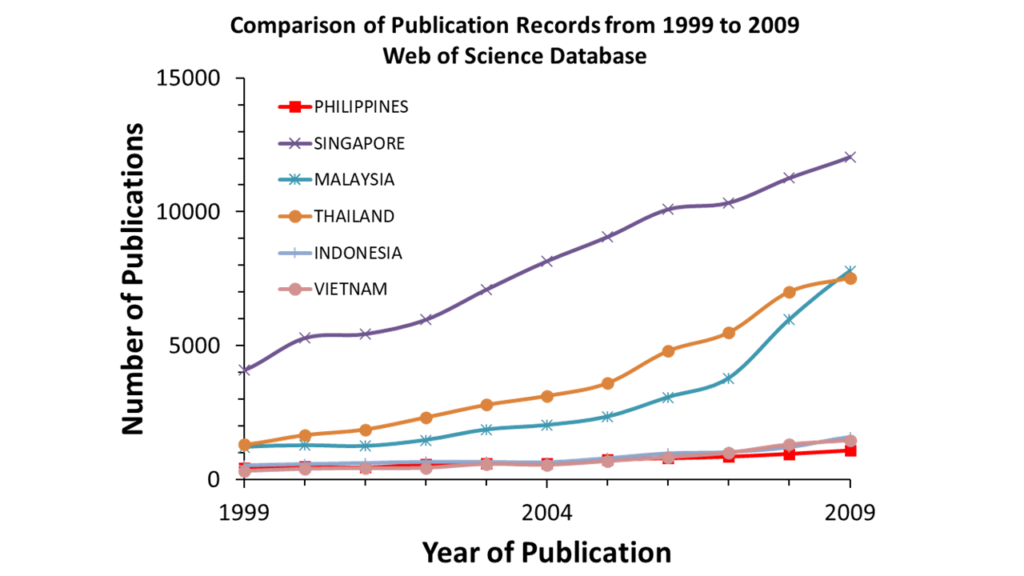

About ten years ago, BKR took the initiative of investigating the status of research productivity of ASEAN countries, using the annual number of publications as a metric for research productivity. The data was culled from a search on the ISI Web of Science database, using a search based on address of all records from 1900s to present day. At that time, the plot we had generated looked something like this:

As shown in Fig. 1, Singapore led the pack by around 12,000 entries in 2009, trailed behind by Thailand and Malaysia at approximately 7,000. Indonesia, Vietnam, and the Philippines had publication records hovering above 1,000 only. (Note: Cambodia, Laos, and Myanmar were excluded due to their relatively lower number of publications compared to the other countries represented in the plot.)

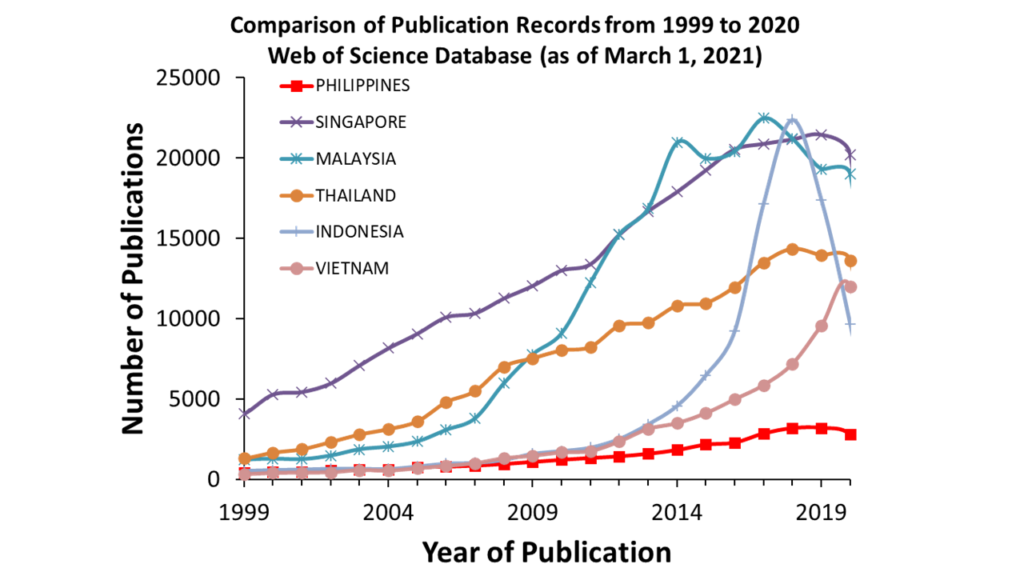

Fast forward to 2020. Replotting the data to include the statistics for the last decade, to our surprise this is what we obtained:

It can be seen that Malaysia has experienced a significant increase in research productivity beginning from 2009 to around 2014, then somewhat plateaued in recent years, nevertheless it has achieved the same level comparable to that of Singapore. Indonesia, on the other hand, showed a dramatic increase which can be seen as a spike which peaked at 2018, reaching the levels of Malaysia and Singapore; however, it appears to be on a downward trend for the last three years. In recent years Vietnam also showed a very remarkable increase and is now almost at par with that of Thailand.

Among all the countries shown in the plot, the Philippines exhibits the slowest growth, and the lowest number of publications hovering at around 3000 for the year 2019-2020.

Based on these plots, it is clearly obvious that whereas our ASEAN neighbors have successfully achieved quantifiable improvements in their research productivity over the past decade, in contrast our country has seriously lagged.

What could have caused this? Why have the other countries like Vietnam and Indonesia succeeded where we could not? What did they do differently? We doubt that it may be correlated solely to the brain-drain problem – this in and of itself is a problem with serious consequences – but several other factors like lack of resources, bureaucracy, and a simple lack of motivation to publish may also contribute to the overall poor performance of the Filipino research community. This is clearly a serious problem, and one that is worth analyzing to determine its root causes and identify ways to mitigate.

According to a recent paper prepared by PAASE (Philippine-American Academy of Science & Engineering, www.paase.org) on the topic of S&T human capital development, we have sufficient Bachelor of Science (BS) graduates in the country, but “not enough Masters (MS), PhDs, and postdoctoral fellows to serve as high-skill researchers in academe, industry, and government.” [2] In the same paper, a comparison of the number of researchers per million population based on UNESCO data for year 2016 – 2017 shows that we have less than 200, which is very low compared to that of Vietnam (~1400) or Indonesia (~540). This suggests that in order for the Philippines to make significant strides in the S&T sector and catch up with other countries in the ASEAN region, first and foremost there should be a strong and sustained effort on improving the number of PhDs and high-skill researchers. Second, there should be a coordinated effort to retain those PhDs and high-skill researchers in universities and institutes by creating attractive and conducive environments for doing research.

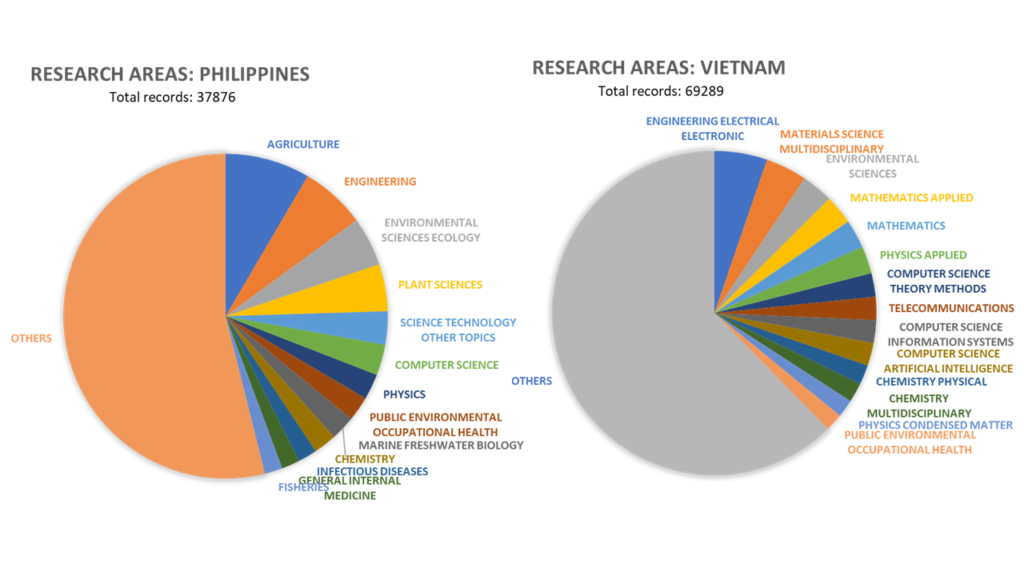

Analysis of the research areas covered by the publications shows that in the Philippines agriculture takes up a significantly large portion, followed by engineering, environmental sciences ecology, and plant sciences (Fig. 3, left plot). By contrast, a similar analysis of the research areas for Vietnam shows that the top areas include electrical engineering/electronic, materials science, environmental sciences, applied and pure mathematics, and applied physics (Fig. 3, right plot). In the same study by Jaffe et al. [1], they mentioned that in one of their earlier analysis it was revealed that countries which have a “higher relative productivity in basic sciences, such as physics and chemistry, had the highest economic growth in the following five years compared to countries with a higher relative productivity in applied sciences such as medicine and pharmacy.” As the chart shows, the basic sciences still occupy a relatively small proportion among the research areas in the Philippines. This comparison suggests that the accelerated research productivity of Vietnam in recent years is likewise driven by its focus on both applied and basic sciences, which is in stark contrast to the research structure being implemented in the Philippines.

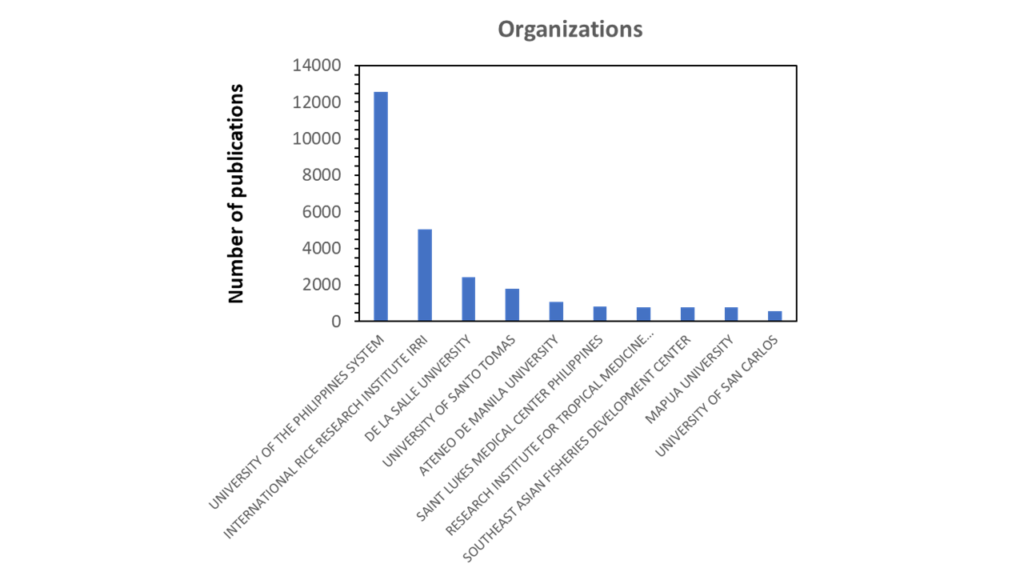

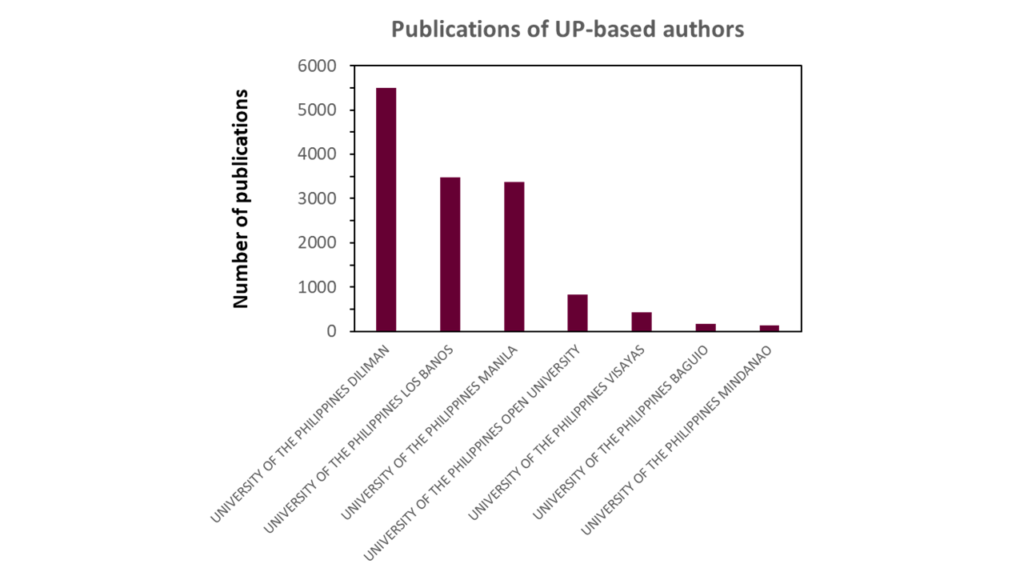

We further extracted the top ten organizations with the highest publication records (total number of publications analyzed: 37,876). The plot below shows that UP System leads the pack with over 12,000 total publications to date, followed by IRRI, DLSU, UST, and ADMU. Five universities in the top ten comprise UP System, DLSU, UST, ADMU, Mapua, and USC. However, it can be clearly seen that there is a big disparity between the performance of UP compared to other universities. This suggests that most of the publications in the country (~ 33%) are generated mainly by UP-based authors. By boosting the performance of state universities and higher education institutes in terms of publishing research results, at least up to par with UP’s, will drastically increase the research productivity of the country. Fig. 5 shows the breakdown of publications by authors affiliated with different campuses in the UP system (note: the cumulative number exceeds that of the UP system shown in Fig. 4 due to multiplicity of records). It is interesting to note that the highest publications are those of UP Diliman, UP Los Banos, and UP Manila, which may indicate a correlation with the personnel size and technological level of those campuses compared to those outside of the NCR.

These numbers may paint a hard reality that is difficult to accept, but this should not be taken as a source of disappointment and disillusionment; rather, it should be regarded as a wake-up call. A healthy awareness of our status is the first crucial step to strive better and seek viable solutions for change. As Filipinos we have time and again shown our resilience despite hardships and difficulties, surely, we are also capable of changing for the better.

The choice is ours.

References

[1] Jaffe K, ter Horst E, Gunn LH, Zambrano JD, Molina G (2020) A network analysis of research productivity by country, discipline, and wealth. PLoS ONE 15(5): e0232458. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0232458

[2] PAASE Recommendations on S&T Human Capital Development, C.P. David, G.P. Padilla-Concepcion, E.M. Pernia, S.L.S. Daway-Ducanes, A.E. Pascual, B.F. Nebres, January 2021. http://www.paase.org