The Hirsch number (otherwise known as the h-index) tries to quantify the (scientific) productivity of a scientist. The Hirsch number was first described by the physicist J.E. Hirsch in a 2005 PNAS paper: An index to quantify an individual?s scientific research output. Hirsch says:

I propose the index h, defined as the number of papers with citation number

h, as a useful index to characterize the scientific output of a researcher.The publication record of an individual and the citation record clearly are data that contain useful information. That information includes the number (Np) of papers published over n years, the number of citations (Njc) for each paper (j), the journals where the papers were published, their impact parameter, etc. This large amount of information will be evaluated with different criteria by different people. Here, I would like to propose a single number, the “h index,” as a particularly simple and useful way to characterize the scientific output of a researcher.A scientist has index h if h of his or her Np papers have at least h citations each and the other (Np ? h) papers have

h citations each.

|

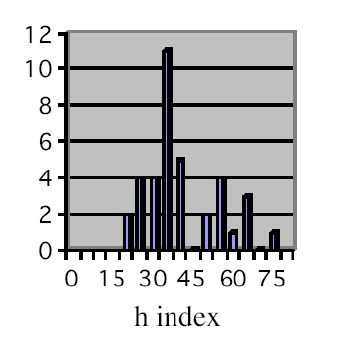

| Histogram giving number of Nobel-prize recipients in Physics in the last 20 years versus their h-index. The peak is at h-index between 35 and 39 (image and text: http://physicsworld.com/cws/article/news/22890/1/050809.) |

For example, if I have a Hirsch number of 10, that simply means that I have written 10 papers with at least 10 citations each.

Most of us are familiar with the impact factor, which is the commonly accepted method for measuring the scientific “weight” of a paper. The impact factor for a journal is “calculated based on a three-year period, and can be considered to be the average number of times published papers are cited up to two calendar years after publication (including the calendar year in which it was published)” (Source: Wikipedia). Currently the top scientific journal with the highest impact factor is Science (30.028) followed closely by Nature (26.681).

J.E. Hirsch further argues in a recent paper that the h-index appears to be a good predictor of one’s scientific productivity in the future.

For those of us who hate quantifying our work, and having ourselves “measured” in terms of simple numbers, it may very well be that the h-index is just another mathematical exercise that we can do without. The thought of having our CVs – our life’s work – reduced to a single number could be unnerving especially to those who are only about to embark on their scientific careers. On the other hand, knowing in advance that such a parameter exists – which could very well be the basis for evaluation in future employment applications – may also help one in mapping out the best strategies for scientific productivity and career advancement.

Hello abner, i just registered and am amazed that there is this BKR blog. am thrilled. just wnated to ask if your question was answered already—- april 2008?

Hi,

I am an electrical engineer by profession. I’ve been doing a research on alternative fuel/biofuel during my spare time. I have a chemical reaction involving waste vegetable oil. I am sure the resulting gas from the reaction is flammable. But I don’t know what kind of gas it is. Can you help me find a chemist or a chemical lab for complete analysis. Thanks.

Pingback:Eric

It was a very interesting article. What I like about his proposed h factor is that it almost completely eliminates erroneous impressions made by a long list of cited minor co-authorships by certain authors.

However, it could have some flaws. Particularly, it invites the rise of cross-citations (i.e. authors indiscriminately citing their own previous works). Just looking at the h factor and not looking at the list of raw citations may show the wrong impression regarding the impact of a published work.

More importantly, this indexing scheme, depends a lot on the popularity (and the number of researchers in that area) of a research field. For example, Manuel Cardona (the grand old man of modern semiconductor physics) had a higher h compared to Stephen Hawking. Off hand, everybody would agree that Stephen Hawking is a celebrity while Cardona is famous only to scientists in his field. Condensed matter physicists “might” outnumber astrophysicists 100:1. This could be the major factor why Cardona had a much higher h value—there are just more competent scientists in his field who would cite his work compared to Hawking. However, the impact factor of astrophysics journals, on the average, are 5 times that of condensed matter physics journals. Clearly, in this case, the h index was not able to provide an accurate comparison between two scientists.

IMHO, this new yardstick proposal may very well be a good complement to raw citation lists and impact factor information of one’s published works. But it may not be a considered as a single defining measure of a scientist’s research output.

Peace.