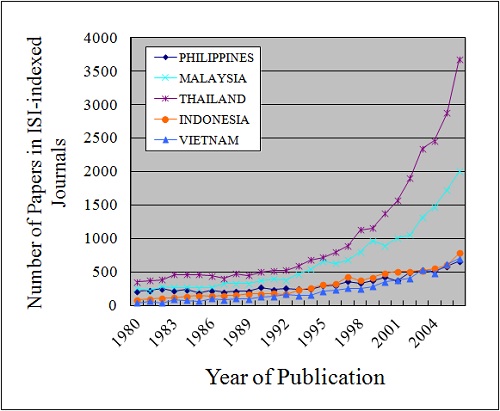

Several years ago, we reviewed the scientific publication performance of the Philippines and some of its neighboring countries including Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, and Vietnam. Using the Science Citation Index Expanded, we looked at the number of publications coming from these countries between 1980 and 2006. See Box 1. Our findings showed that Malaysia and Thailand were already ahead of the Philippines in 1980, but the Philippines was still ahead of Indonesia and Vietnam. By mid 1990s, Indonesia had overtaken the Philippines, and by mid 2000s, Vietnam had overtaken the country as well. The data also showed that the Philippines had the lowest publication growth rate of all countries considered.

|

| Publication of 5 ASEAN countries between 1980 and 2006 |

Fast forward to 2011, a similar publication review [1] is recently published in Scientometrics. The authors examined the scientific output of the 10 members of the Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN) including the countries mentioned above plus Brunei, Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, and Singapore. As a measure for scientific output, they used bibliometric data from the Institute of Scientific Information (ISI) and analyzed the number of scientific articles published in peer-reviewed journals between 1991 and 2010. Furthermore, they also examined the relationship between scientific output and the knowledge economy index (KEI), an indicator measuring the country’s position in the global knowledge economy.

In terms of publication output, the paper’s findings showed that researchers from ASEAN countries have published 165,020 articles in ISI-indexed journals, roughly 0.5% of the world’s scientific output. Based on the number of publications, ASEAN countries can be clustered into four groups with Singapore producing 45% of the total publications in one group, then Thailand with 21% and Malaysia with 16% in the second group. The third group is comprised of Vietnam with 6.5%, Indonesia with 5%, and the Philippines with 4.6%. Finally, Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, and Brunei are in the fourth group with a cumulative output of 1.6%.

The authors also reported a steady increase of publications between 1991 and 2010 in all countries considered, with an average increase of 13% per year. Thailand had the highest rate of increase, which is 15% per year. Indonesia and the Philippines had the lowest rate of 8% each. When the covered period is divided into two, one from 1991 to 2000 and the other from 2001 to 2010, Laos and Cambodia showed highest increase rate of 9.15 and 9.07 times, respectively. On the other hand, the Philippines and Brunei had the lowest increase rate of 1.88 and 1.64 times, respectively.

As we’ve observed in our initial review five years ago, there has been an increasing disparity among ASEAN countries in terms of scientific output. Sadly, this still holds true at present. The most progressive Singapore is now way ahead on top, with Thailand and Malaysia catching up. The Philippines had been ahead of Indonesia and Vietnam in the early 80s. But by mid 2000, Vietnam has overtaken the country and the gap is alarmingly increasing. Being ranked as the second to the lowest increase rate among ASEAN countries, the Philippines may well soon end up at the bottom, unless some concrete actions will be done to halt it. Come to think of it, this is not that far-fetched an outcome. With the highest rate of increase in the number of publications, Cambodia could overtake the Philippines by 2020.

But why should we care? Why waste our limited financial resources on science and technology (S&T) and research and development (R&D)? Do we really need to invest on S&T and R&D? What has the number of publications got to do with the basic needs of the people like food, water, and shelter? Well, according to a 1996 OECD report [2], knowledge “is now recognised as the driver of productivity and economic growth, leading to a new focus on the role of information, technology and learning in economic performance.” The term “knowledge-based economy” stems from this fuller recognition of the place of knowledge and technology in modern economies.

To relate the country’s scientific output to its position in the global knowledge economy, the paper used two indicators: knowledge index (KI) and knowledge economy index (KEI). The knowledge index takes into account the country’s overall potential of generating, adopting, and diffusing knowledge. On the other hand, the knowledge economy index measures whether the the country has an environment conducive to effectively use knowledge for economic development. Both of these indicators are based on the four pillars of knowledge economy, namely economic incentive and institutional regime, education and human resources, innovation system, and information and communication technology (ICT) [3].

In terms of these indicators, the same grouping among ASEAN countries was observed. Singapore was ranked highest, followed by Malaysia and Thailand, then the Philippines, Vietnam and Indonesia. The Philippines’ knowledge economy index and knowledge index are 4.12 and 4.02, respectively (10 being the highest). A strong linear correlation was observed between the number of scientific publications and KEI (0.96) and between the number of publications and innovation (0.94). This means that countries with higher KEI have also higher scientific publication output.

This high correlation, however, does not imply a causal relationship that would have answered the question of whether an increase in scientific publication leads to economic development and vice-versa. There was just not enough data to examine this. But what is evident is that knowledge has now become an important driver in productivity and economic growth and has become as critical as other economic resources. And in this modern economy, the scientific enterprise plays a very important function, particularly in the generation, dissemination, and transfer of knowledge.

In the Philippine context, it is therefore imperative for the government to invest more in scientific research, for educational/research institutions to become active players not only in the transmission of knowledge but also in the generation of it by encouraging faculty and staff members to be actively involved in research, and for Filipino researchers to publish their research results to contribute in the generation of knowledge. A synergistic approach would be necessary to reinvigorate our S&T and make the country at par with its ASEAN neighbors, if not better. Our downward spiral is alarming, and in the absence of concrete steps to stop it, the Philippines would soon be found at the bottom of the heap. Clearly, if we want change, there is no better time to act than NOW.

The question that remains is this: are we willing to face the challenge?

References:

[1] Tuan V. Nguyen and Ly T. Pham, “Scientific output and its relationship to knowledge

economy: an analysis of ASEAN countries,” Scientometrics 89 (2011), pp 107–117.

[2] http://www.oecd.org/dataoecd/51/8/1913021.pdf

[3] http://go.worldbank.org/SDDP3I1T40

I believe we have a lot of good researchers and study makers, what sad is, we have no budget in making scientific studies.

Pingback:Filler 10C: UP Diliman and top National Universities in the Region, etc… «

Philippines is obviously ignoring these statistics and focusing on chasing shadows like impeachment trials. As a nation, Philippines has no scientific contribution to the world but its people remains arrogant of a once glorified past. The government has just increased its budget for social welfare and is currently training its citizens to be ass wipers of the world.